- Only once was the #Mets opening-day starter under 21. In 1985, in his second season with the Mets, Dwight Gooden left the game in the 7th inning. The Mets won the game, 6-5, in the bottom of the 10th, on a Gary Carter home run off ex-Mets pitcher Neil Allen.

- Whereas Dwight Gooden was the Mets youngest opening-day starter, Bartolo Colon and Tom Glavine were the oldest. Both were in their forties, Colon appearing once (2015) and Glavine twice (2006, 2007). In every game, they pitched six innings, gave up one earned run, and won the game. In Colon’s start, the losing pitcher was Max Scherzer.

- The Mets have played 60 opening games, winning 29. Jacob deGrom has been named the starter in the 2022 opener, his fourth consecutive opening-day start. In his previous three, he won two, the no-decision start in 2021. In all three games, in 17 IP, he did not give up a run.

- In the Mets 60-year history, on Opening Day the opposing starter has been left-handed 15 times. The last time, last year, the Mets lost 5-3. Before that, they had not lost on Opening Day against a left-handed starter since 1974. On April 7, the Nats expected starter is Patrick Corbin, a LHP.

- On Opening Day from 1962-2021, the Mets have played 14 teams. They have played the Phillies the most, nine times, winning six and losing three, and have never lost a home opener to the Phillies, winning all five games.

- The last time the Mets stole a base on Opening Day was in 2018. In the bottom of the fifth, Jay Bruce stole second base. The Mets won the game, 9-4, against the Cardinals. Travis Jankowski stole second in a season opener in 2020 with the Reds. View Stathead Results.

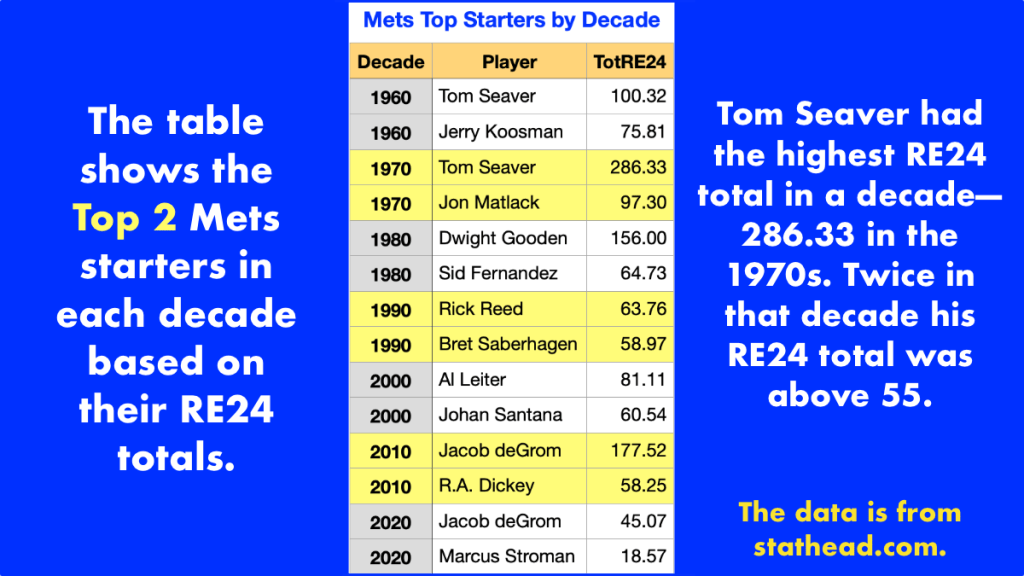

- Two Mets pitchers started almost one-third of the team’s Opening-Day games. Tom Seaver started in 11 of them, winning eight, and Dwight Gooden started in eight, winning seven. @baseball_ref

- Baseball Reference contains the Opening-Day lineups for all Mets opening games.

Updated April 5, 2022