When writing about a sports event, Runyon did not just view it through a wide-angle lens but varied the view, zooming in and focusing on aspects other writers omitted.

As Brian O’Connor wrote in an article in The Irish Times with regard to Runyon’s writing about horse racing, “The Racing World of Damon Runyon, published in 1999, contains umpteen picaresque characters crammed with the peccadilloes and prejudices that immediately define the age from which they emerged.”

Though the book contains short stories, their style shares a Runyonesque-ness with his best sportswriting.

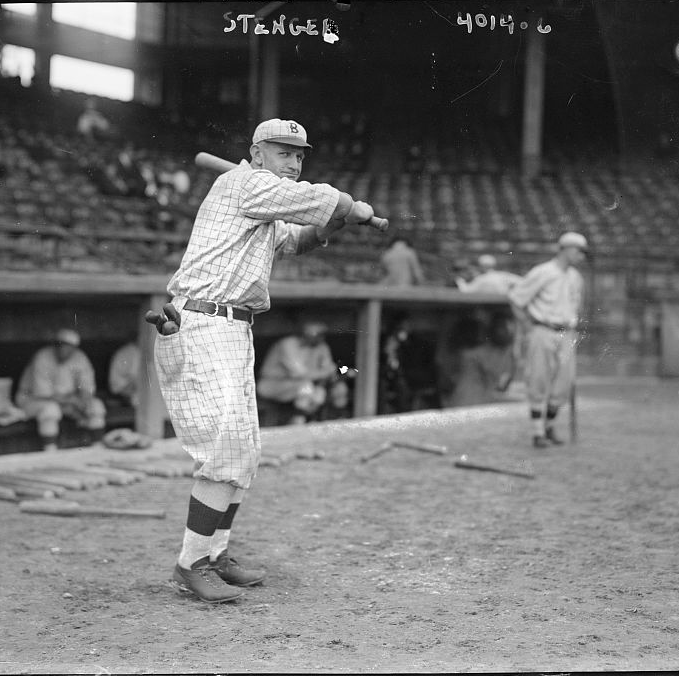

Here is a sample of Runyon’s sportswriting, quoted from his story, “Stengel’s Homer Wins It for Giants, 5–4” in The Great American Sports Page:

This is the way old “Casey” Stengel ran yesterday afternoon, running his home run home.

This is the way old “Casey” Stengel ran running his home run home to a Giant victory by a score of 5 to 4 in the first game of the World Series of 1923.

This is the way old “Casey” Stengel ran, running his home run home, when two were out in the ninth inning and the score was tied and the ball was still bounding inside the Yankee yard.

This is the way—

His mouth wide open.

His warped old legs bending beneath him at every stride.

Runyon repeats “This is the way” four times: It is an anaphora. He also repeats “This is the way old “Casey” Stengel ran, running his home run home” three times. By “running his home run home” Runyon is emphasizing the fact that Stengel ran full-speed around the bases because his hit never reaches the stands: It is an inside-the-park homer. Normally, a homer leaves the playing field, and the hitter trots around the bases without any urgency.

An anaphora’s literary overtone adds a dimension to his piece not often associated with “sports writing.” The repeated words draw attention and effect a rhythm whose beat deepens readers’ engagement as Stengel’s “warped old legs” propel him round the bases toward victory for the Giants.

John Schulian, in The Great American Sports Page, wrote this about Damon Runyon:

“He came from Colorado in 1910 to report on baseball for William Randolph Hearst’s New York papers, but the press box could hold him for only so long. He went on to cover murder trials by applying the techniques of baseball writing and to capture the vernacular of the streets in the short stories that came to life onstage as Guys and Dolls. Ever since then, writers have tried to duplicate the rhythms in the sentences Runyon left behind. They never come better than close.”

One of my favorite Damon Runyon short stories is “Baseball Hattie,” a tale in his book, Take It Easy, that exemplifies Runyon’s unique writing style. “Baseball Hattie” is both a story in Runyon’s book, Take It Easy, and one of its star attractions.

When the story’s anonymous narrator sees Hattie, an every-game fan, for the first time in years at a baseball game on opening day at the Polo Grounds, the Bronx home of the New York Giants before they deserted the Big Apple for San Francisco, he spells out the differences:

“I can see that Baseball Hattie is greatly changed, and to tell the truth, I can see that she is getting to be nothing but an old bag. Her hair that is once as black as a yard up a stove-pipe is grey, and she is wearing gold-rimmed cheaters, although she seems to be pretty well dressed and looks as if she may be in the money a little bit, at that.”

But the biggest change is that Baseball Hattie is not loud-mouthing Umpire William Klem, her preoccupation whenever the narrator had previously seen her in the stands. The seed of that change happened years before at an away game in Philadelphia, which is where Hattie first met a “big, tall, left-handed pitcher by the name of Haystack Duggeler.”

After the narrator calls Hattie “a baseball bug” and explains why, the story time-travels backwards to fill in the readers’ gaps and to enable the story’s surprising ending to make sense.

And what a trip that is.

Be forewarned that Runyon, in his short stories, avoids the past tense as if its use would trigger a severe allergic reaction. Further, he has eliminated these words from his dictionary: would, should, could might. Plus, he loves to slip slang into his sentences, sometimes even inventing the language addition, an action that can jar a reader’s journey through Runyon’s thoughts though generally that is an easy task. Finally, Runyon is funny, so be prepared to laugh aloud as his writing can have a ticklish effect, so if that can be embarrassing for you, consider sheltering yourself when you are riding his train.