Tag: Sports

MLB No-Hitter Facts

As of June 21, 2024, 284 no-hitters have been thrown in Major League Baseball, per Stathead, using this criteria: “From 1901 to 2024, in the regular season, requiring Hit Allowed = 0 and Runs Allowed =0.”

The first no-hitter was on June 30, 1901. Cleveland (Blues) played the Milwaukee Brewers before a crowd of 4,500. While the Brewers were hitless, Cleveland’s baserunners crossed the plate seven times during an afternoon in which the team got 18 hits but, surprisingly, just one walk.

In the Brewers’ lineup were four players whose first name was either Bill or Billy. Even more interesting is that the home plate umpire was the game’s only umpire.

The 1901 season was not a good one for the Brewers. Their game against the Blues was their 56th of the season and they were in the midst of an eight-game losing streak, one in which they had been shut out in their previous two games, their June 30th loss worsening their record to 19-36-1.

It was a no-hitter that, for many years, wasn’t.

SABR devoted an article to the game, explaining why. In it is stated, “This is the story of that confounding game and the baseball community’s century-long journey in finally recognizing Dowling’s gem as a no-hitter.”

One reason it’s “confounding,” according to its author, Gary Belleville,” is that “At the start of the twenty-first century, baseball’s consensus was that Jimmy “Nixey” Callahan had thrown the American League’s inaugural no-hitter, in 1902, and Bob Rhoads had tossed the first one for the Cleveland Indians franchise in 1908,” not Pete Dowling, who was on the mound for Cleveland on June 30, 1901.

After that game, Cleveland pitchers threw 12 more no-hitters, tying them for fourth place in most no-hitters thrown. One was thrown again on June 30, but 47 years later in 1948. Bob Lemon beat the Tigers 2-0, the Indians scoring both their runs in the top of the first on Lou Boudreau’s double.

After the game, Lemon’s batting average was .347. He finished the season with a .286 batting average, the second highest of his career, which was the same as Whitey Lockman’s and higher than Dom DiMaggio’s.

In Lemon’s SABR bio, Jon Barnes wrote that Lemon “was one of the best hitting pitchers ever in the majors.” He also pitched well enough to earn a spot in baseball’s Hall of Fame.

Wanted: Third Baseman

Rylan Bannon by the Numbers

With a hole at the hot corner that has heated up with Ronnie Mauricio’s leg injury, a probable product of his playing spring, summer, fall, and winter ball, the Mets have invited a former high school second baseman who was the Big East Player of the Year in 2017, Rylan Bannon, to spring training.

After homering 15 times in his last season playing for the Xavier University Musketeers’ baseball team, he dipped into the double digits in homers in every season since, including 18 for the Sugar Land Space Cowboys, the PCL team with the lowest won-loss percentage in 2023, a fact Bannon’s resume is unlikely to mention.

His home run total, however, was the third most on the team in a league where it is common for batters to touch all four bases on a hit, 68 hitters doing that at least 10 times last season — 12 played third base.

Bannon didn’t just draw attention with his bat; he also showed skill on the basepath, stealing 12 bases, tying him for the league lead among third basemen.

In the field, in 479.2 innings at third, he made just five errors while notching 85 assists.

Bannon’s presence in spring training should increase the competition at a position where the Mets again do not have a proven “name” vying for the everyday job at third.

Writing About Sports: Stengel At Bat

During Casey Stengel’s 14-year playing career, he stepped into the batters box 4,871 times; however, six at bats stood out.

First At Bat: Sept. 17, 1912

On September 17, 1912, Casey Stengel made his major league debut at Washington Park, a ballpark located in Park Slope, a Brooklyn neighborhood. According to Barry Petchesky, “From 1898 to 1912, Washington Park was the home of the team alternately nicknamed the Bridegrooms, Superbas and Trolley Dodgers,” though in the game’s boxscore, the team is called the “Brooklyn Dodgers.”

Petchesky wrote, “The field did not seem to be beloved in its time. The nearby canal gave off a constant stench, and as a late-season call-up, Casey Stengel, once remembered, “the mosquitoes was something fierce.”

Batting second and playing centerfield, Stengel singled in his first at bat. In the game, he got four hits in four at bats, all singles, walked once, drove in two runs, stole two bases, and had a putout. He finished his first season with a .316 BA, .466 OBP, and .852 OPS.

The Sporting News exclaimed: “Charlie Stengel has come into the league with a tremendous crash, and appears to be the real thing.”

Stengel played the most years with the Brooklyn Dodgers (6) and the New York Giants (3); however, at the plate he was most successful with the Giants, averaging .349/.413/.524.

On the basepath, he showed both smarts and speed. In both 1913 and 1914 with the Brooklyn Dodgers, he stole 19 bases in an era when base theft was commonplace. In 1913, the Dodgers had 188 stolen bases and in 1914, 173. In both seasons, seven Dodgers stole at least 10.

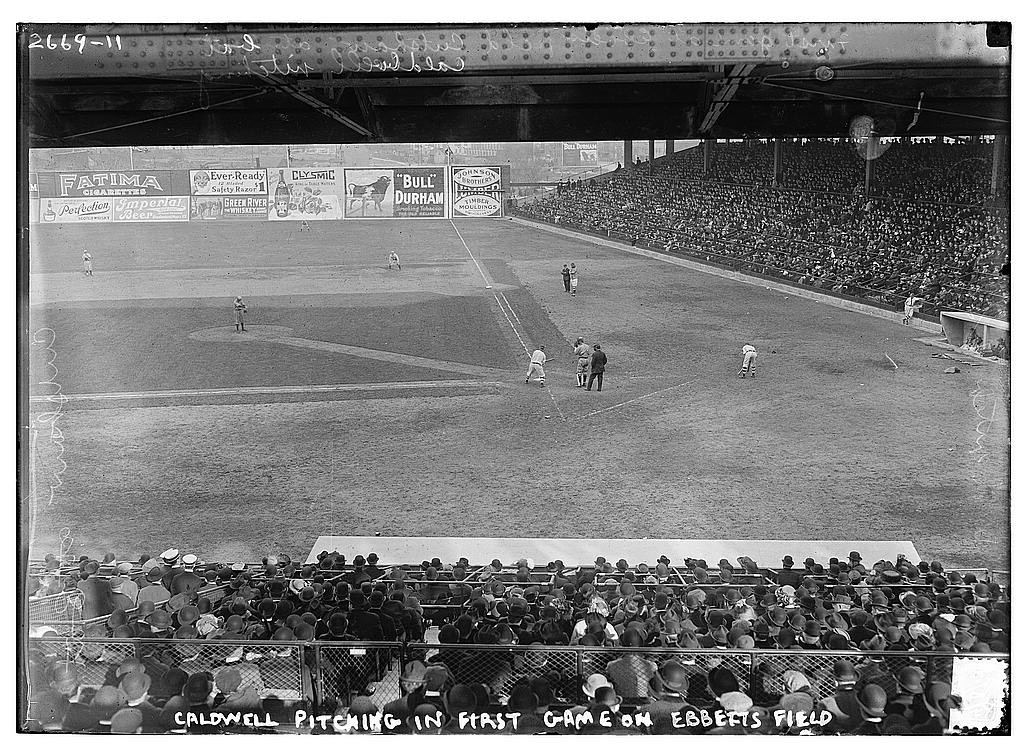

Second At Bat: April 5, 1913

Three weeks after hitting the first home run at Ebbets Field in the new ballpark’s first game—an exhibition against the Yankees, Stengel hit the first four-bagger in a regular season game at the Flatbush ballpark. The Brooklyn Superbas, as the Dodgers were then known, defeated the Giants, 5–3.

Third & Fourth At Bats: May 1, 1913

Stengel is among a select group of players who hit two inside-the-park homers in the same game, notching that feat on May 1, 1913 while batting leadoff for the Brooklyn Superbas. In a New York Times writeup of the game, the story’s headline declared “STENGEL’S HITTING LANDS CLOSE GAME,” its author, unidentified, referring to him as “Charley Stengel.”

The first blast reached the “centre field wall.” No mention is made of it being a close play unlike his second four-bagger to “deep left centre.” It “just grazed the tips of glove of Outfielder Manns’ as it hurried along to the outfield wall But because of Boston’s defensive effort, “Stengel barely made the circuit.”

Both homers were off Otto Hess.

The last time a major leaguer hit two inside-the-park homers in a game was 1986. Greg Gagne hit two and just missed a third. On his last try, he had to settle for a triple.

Fifth At Bat: May 7, 1923

The fifth at bat showed that Stengel could not only hit with a bat but also with his fists.

On May 7, 1923, the New York Giants played in Philadelphia, the team for whom Stengel played in 1920 and part of 1921 before being traded to the Phillies. On the mound for the Phillies was Lefty Weinert, who had been with the team since 1919.

In Stengel’s first at bat against Weinert, instead of using the bat to hit the ball he used it as a weapon. According to a New York Times news report published on May 8, this transpired:

The fight in the fourth was precipitated by a belief on Stengel’s part that Weinert had tried to “bean” him. Thoroughly aroused, Casey threw his bat in Weinert’s direction and then rushed out to the box. In an instant the two players were swinging at each other, while other players of both teams gathered around them and policemen poured out of the stands.

Robert Creamer, in his book, Stengel: His Life and Times provided more details about the fight.

“The Giants scored six runs in the first inning (Stengel drove in one of them with a single) and knocked out the starting pitcher. A left-hander named Phil Weinert came in to pitch for the Phils. Weinert was big and fast and wild. He hit Casey with a pitch in the second inning, and when Stengel came to bat again in the fourth Weinert threw a fastball close to his head. Casey threw his bat angrily at the pitcher and ran toward him. Weinert was four or five inches taller than Stengel, outweighed him by twenty pounds and was more than ten years younger, but when they tangled and fell to the ground Casey was on top, swinging. Art Fletcher, a former Giant shortstop who was managing the Phils, grabbed Casey with a forearm under his chin and dragged him away from Weinert. Stengel struggled to get loose and back into the fight, but several policemen came on the field and two of them took Casey in hand. Still fuming, Stengel reluctantly allowed himself to be taken off the field. Next morning he learned that he had been suspended for ten days by National League president John Heydler.”

Stengel’s affinity for fighting with his fists did not end when his playing career did. While managing the Brooklyn Dodgers in a game at Ebbets Field, he fought with St. Louis Cardinals’ shortstop Leo Durocher in the“runway behind the dugout,” according to Roscoe McGowen in the May 13, 1936 edition of The New York Times.

Sixth At Bat: October 10, 1923

The first player to hit a World Series home run at Yankee Stadium was not Babe Ruth. It was Casey Stengel who, in 1923 played for the New York Giants, their home field the Polo Grounds, a ballpark that the Yankees played in from 1913 through 1922.

That homer ranks as one of Stengel’s biggest baseball moments as a player. Damon Runyon memorialized it in his story, “Stengel’s Homer Wins It for Giants, 5–4,” which I wrote about here.

Runyon’s piece began with these lines:

This is the way old “Casey” Stengel ran yesterday afternoon, running his home run home.

This is the way old “Casey” Stengel ran running his home run home to a Giant victory by a score of 5 to 4 in the first game of the World Series of 1923.

Stengel’s inside-the-park homer in the ninth broke a 4–4 tie. He was 32-years-old. Only two teammates, Hank Gowdy and Heinie Groh, were older.

In the bottom of the ninth as the Giants returned to their positions to defend their lead, Stengel did not leave the dugout. Instead, Bill Cunningham headed toward centerfield.

It was the ninth time the Giants and Yankees had met in a World Series game, and the ninth time the Yankees did not win.