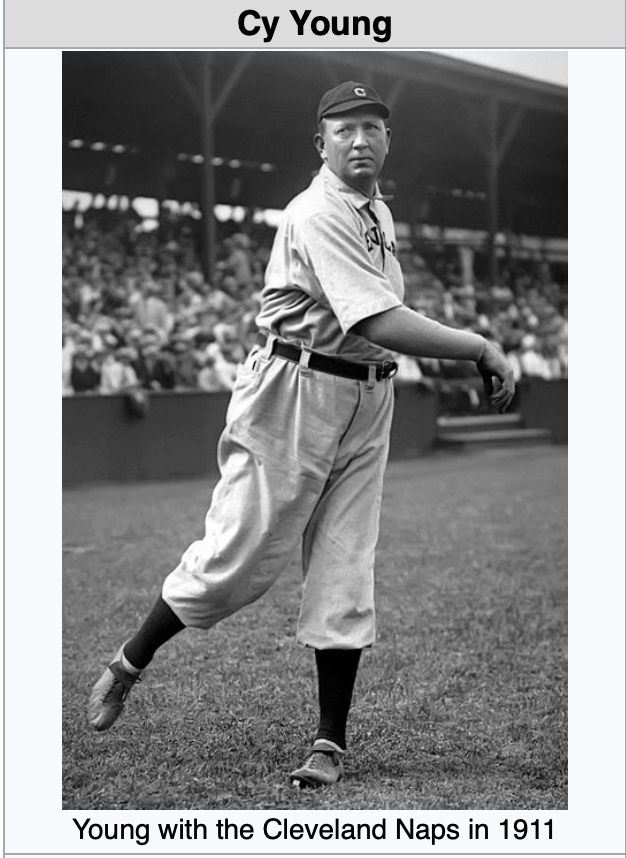

For more than 60 years, baseball has recognized its mound stars with a plaque that memorializes the achievements of a man whose 22-year career began in 1890.

When he retired at age 45, Denton True “Cy” Young had won 511 games and, until his next-to-last year in 1910, never lost more games in a season than he won.

Young’s greatest achievement may have come on May 5, 1904, when at the age of 37 he pitched the first perfect game in American League history – just the third in the major leagues and the first from the 60-foot-6-inch pitching distance.

https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/dae2fb8a

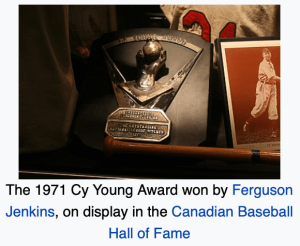

Young died in 1955. A year later Major League Baseball awarded the first Cy Young Award, to Don Newcombe, who got 10 of the 16 first-place votes.

Since Newcombe, 117 more pitchers have won the prize.

During those first 11 years, just one pitcher won it more than once. Sandy Koufax won it three times. While others won it three times, only Roger Clemens (7), Randy Johnson (5), Greg Maddox (4), and Steve Carlton (4) won it more than three times.

Koufax was also one of five winners who pitched for the Los Angeles Dodgers, the Dodgers winning the prize five years in a row.

Further, five of the first 11 winners made it to the Hall of Fame: Warren Spahn, Early Wynn, Whitey Ford, Don Drysdale, and Sandy Koufax.

In 1966, Koufax was the last sole winner in a season. After his final receipt of the award, it was given to the best pitcher in each league.

Cy Young won 477 complete games, fully 60 more than Walter Johnson. Only five times did he win a game that he had started but not completed.

At first, those winning it were starters who had won at least 20 games. That ended in 1973 when members of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America awarded it to Tom Seaver though he had a 19-10 record.

A year later, the first reliever won the Cy Young. Mike Marshall, pitching for the Los Angeles Dodgers, finished the 1974 season with a 15-12 record. He stood on the mound in 106 games, 30 more than Rollie Fingers, and pitched in 208.1 innings, starter’s numbers. So he averaged just under two innings a game. Despite all those appearances, his ERA was just 2.42.

Though Marshall had 21 saves, he did not lead the lead in that category, coming in second to Terry Forster who had 24 in 59 games. Despite being the runner-up in saves, Marshall was named the The Sporting News’ Fireman of the Year.

After Marshall, eight other relievers have won the Cy Young, but none since another Dodger, Eric Gagne, received it in 2003.

Among all pitchers, both starters and relievers, only 11 have won the award in back-to-back seasons. Among them is Jacob deGrom, Mets standout, who received it in both 2018 and 2019, winning 21 games. However, unlike Gaylord Perry, those wins were not in one season but two, 10 in 2018 and 11 in 2019. Those two win totals were the lowest ever for a Cy Young Award winner who was a starter.

Cy Young threw a baseball until his right arm could no longer obey his mind’s commands.

“All us Youngs could throw,” he said. “I used to kill squirrels with a stone when I was a kid, and my granddad once killed a turkey buzzard on the fly with a rock.”

https://www.baseball-almanac.com/quotes/quoyung.shtml

He was inducted into baseball’s Hall of Fame in 1937.

On his tombstone, above his name and that of his wife, is a winged baseball.